Neil Welliver [1929-2005] is a painter whose work I undoubtedly had seen at earlier points in my life, but it wasn't until I came across a copy of Welliver [New York: Rizzoli, 1985, with Introduction by John Ashbery, and text by Frank H. Goodyear Jr.] that I consciously discovered the originality and power of his vision of New England landscape. Representation, or "figurative" art, has had an uncertain place in the history of the development of art since the end of the 19th Century. Since the changes brought about by European innovators in the early years of the 20th Century, the "imitation" of nature has tended to be regarded as secondary to the pursuit of Abstraction (for its own sake). To be caught "in the wrong century" has been the fate of many highly skilled and speculative artists--artists whose abilities and proclivities might have been better suited to the traditions of earlier eras and styles along the time-line of history. But there have been a few--and Neil Welliver is clearly one of this group--for whom Abstraction provided an alternative approach to straight representation, offering them tools or methods which might be employed to emphasize aspects of technique which seemed rather "anti"-representational, while actually being closer to how perception (or seeing) actually works or feels to humans.

Originally beginning as a doctrinaire abstract color field painter, Welliver in due course developed into a landscape painter, focusing on intimate rural or wilderness plein-air scenes, in and around Maine. Frequently working at a large scale--some of his canvases are as big as the wall of a single small room--he evolved a strikingly vivid approach which emphasized the freshness, crispness and drama of natural settings.

Welliver's canvases are immediately apprehensible as intensely seen visions of textures and high-contrast arrangements of wood, water, rock, sky, and the occasional animal or human, portrayed with a studied, muscular determination that is at once shocking, and obdurate. The mood, however, is almost always serious, even gloomy. The concentration of highlighted bands or sinuous stripes of water, snow, roots or sky against darker banks of ground, moss, foliage, etc., creates highly defined matrices, or templates of tone or eccentric grids almost as if these had been superimposed upon a receding perspective.

Our ability to pick out visual queues from a scene, to establish the depth of field in a random "wild" scene is based on our experience of how shape, shadow and mass organize into the cone-shaped vortex which comprises the normal visual matrix. In Welliver's pictures, the intensity of the highlights is slightly exaggerated, so that intensely bright matter, such as water (below) is spread evenly, without any elaboration or gradation, across a receding perspective, creating a sense of layering which suggests the successive laying down of stepped applications, as in a silk-screen printing regime. This aspect is reinforced through the monotony of single palette applications to distinct regions of the composition, i.e., the dark dove-grey stone in the foreground, and the dull lime-green forested area in the background. We have no trouble "reading" the scene for what it is, but the artist's approach is to heighten our sense of the sinuous inertia of the little rapids, the caressing of the rocks as the water slides over them--water becoming, indeed, almost a condition or metaphor for water, clear channels of sense routed along a wholly inevitable terrain.

Pellitier Brook 1994

Cezanne had shown how our seeing is made up of the combination of bits of color along the spectrum of the visual, how shape may be defined by that color, even while it undergoes a slightly augmented or exaggerated transformation. The purposes to which such augmentations might be put have been one of the great vistas of figurative work over the last 75 years.

Modernist and Post-Modernist artists have even made a fetish out of the suggestiveness or suggestibility of the materials of the surface itself, using clever brush-strokes (even the stroke itself as with Lichtenstein, or Warhol) or layering of pigment. But Welliver refrains from implicating technique with the violation of the figurative compact. Things are what they are, they are what they seem. The manipulations of the surface representation of the actual world are employed in the service of a mind intent on reporting what has been seen, and the augmentations all dove-tail into our desire first to see, and feel, the original phenomenon (scene), and perhaps secondarily to revel in the pleasure of the medium as an object in itself.

One of the ways of manipulating a scene, against the flat field of the canvas, is to eliminate depth entirely, creating a two-dimensional grid. If the painting is a window, the invisible glass through which we see "reality" is limited by our inability to pass into or through the glass into the world being depicted. Playing with this "flatness" is one way to emphasize the plane of organized patterns that may occur in nature. The image below is really nothing more than the expression of three colors against a totally flat, white surface. Remove the black bark details, and the white trunks are just random voids, translucent bands like blinds against the "background."

I got to wondering, in looking at Welliver, who else had tinkered with planar templates this way, and recalled the following image from the work of Escher. Escher [1898-1972], as almost everyone in the civilized world by now knows, was an eccentric Dutch artist made famous by his perspective visual conundra, riddles of scale and apprehension. The image below is a fairly straightforward presentation, which is made more vivid and intense through the deliberate emptying out of minute detail, so that the reflected upsidedown perspective is made crisper and perhaps slightly surreal by the sharpness of the contrast. By narrowing the scale of tones, and removing all evidence of expected movement and action, the frozen contradiction of the scene becomes a kind of conceit--a quality completely familiar to all of Escher's work. It's like a mathematical equation, but without any of the properties of change which makes real life so intractable and stubbornly elusive.

Puddle 1952

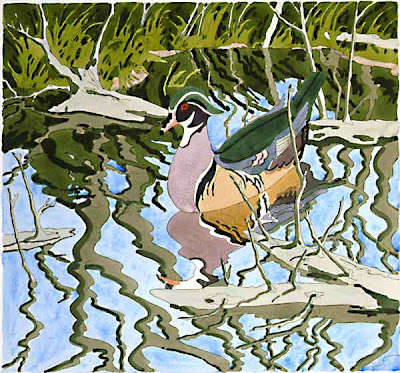

Water surfaces are a natural metaphor for the mirror-image flatness of the surface field. Things seen in water, at an angle, undergo a distortion, as a result of the bending of light, in much the same way that things represented on a canvas may be subtly skewed to bring out a certain aspect of attention or regard. Looking at the canvas below, the "wood duck" is another visual pun on the wooden lifelessness of the work of art itself. Things as they are are changed by the artist's vision, manipulated into an arrangement of color planes, masses and shapes which organize according to a principle made up partly of what we do see, and partly of what our mind prefers to see (or remember) of what it perceives. We know the work of art is flat, and we know the water isn't composed of jagged, sinuous puzzle-like fragments of light blue, shades of green, just as we know the duck isn't real, though it "looks" like a duck, and probably would quack like a duck (if it could), and probably is gently moving its light orange webbed feet under its body in the water, if it has any feet. These are all kinds of pacts we make with art, artists, and indeed with reality itself. We know what water is like, and we've all seen ducks (though perhaps never this close in "reality").

The objectification of landscape in Welliver's Maine scenes is like a perfected regard. It is both the landscape that we would like to think exists, and in a sense it is the landscape. What you feel in these landscapes is the rush and awe and snap of the existential awareness of being-in-the-world. A painting can't report the slipperiness of walking on wet rock, the mossy feel, the sandpapery surface of weathered bark, the fresh wet rotty smell of forest mulch, the tinkle and shurr of brook and rivulet, or the little sway of jeopardy when wind gently rustles the branches high over your head--these things are closed to the visual. But it is possible, as Welliver has done, to heighten our sense of the visual as reported, through the shrewd technique of art, to offer a version of that experience, to create an analogue of that other reality we experience with our bodies, and objectify it, and save it, and give it a kind of repeatability, which is all we know of "permanence."

Escher was keenly aware of the implications of our fetishization of art to represent the real world of experience; he took that tendency to a limit, in making a series of visual riddles, many of which seem childish or obvious. In the image below, the fish swimming under the surface of a pond or lake lives in another reality from that in which the viewer does. The surface of the water is a screen which both separates the viewer from the "other" reality depicted in the scene, and from the reality which art can never truly capture.

Man's place in a universe of his own making has a Heisenbergian ring. The characteristics of the visual reality which we "know" from experience may be enhanced and augmented by our ability to posit variations in the texture of actual light and how it is "reported" to our minds. Looking at the water abstraction below, within which the woman below floats, we "know" that the blue ribbons diagonally ranged across the ruffled plane of the water surface aren't "really" water, but we accept that they stand for water, or are an ingenious metaphor for how water looks in such-and-such a state, under such-and-such conditions. Vickie is under something which we know is a picture of water, a conceptual version of a disturbed surface plane, of a liquid we assume is water. Do we feel its coldness? Do we accept that these blobby blue masses in the foreground mean it's a surface, rather than an empty depth? We assume, too, that the bottom half of Vickie's body conforms to the expected shape and mass of her physical being, and has not been--despite the distortions both of actual light through water--as well as through the surface of the painting as manipulated by the hand of the seer (artist)--changed somehow, or simply is to be inferred from the reassurance of assumption.

Vickie 1970

Escher was interested in "illustrating" certain principles of perceptual phenomena, but he rarely attempted to mimic the qualities of actual seeing, of actual scenes. That lack of immediacy of being-in-reality is probably a weakness of his art, one of the reasons his art will always be regarded as a kind of novelty, despite its wide and immediate appeal.

Confronting the immediacy of our experience of nature in a relatively undisturbed state raises all kinds of other questions, to which art has no immediate answer. Welliver clearly saw and felt things in the Maine outback which suggest the meditative sense-of-being in the world that seemed unique to his apprehension. He sought to convey that immediacy through the exploration of figurative techniques which border on pure abstraction, but which are never allowed to contradict our assumptions about where we are, and what we see. Instead, they enhance and emphasize and reveal aspects of our augmented and intensified experience of the world, which the artist experienced in the real Maine. They are true additions to nature.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar